When most programmers think about object-oriented programming (OOP), they usually remember languages like Java or C++ where a class is a static template for creating objects, inheriting attributes and methods into the created object.

“If you’re creating constructor functions and inheriting from them, you haven’t learned JavaScript” — Eric Elliott

As we saw before, JavaScript doesn’t have classes, but it has an inheritance system that’s more simple, flexible, and powerful.

The word “inheritance” can be a bit misleading, since it implies that behavior is being copied — which doesn’t happen in JavaScript. That’s why Kyle Simpson, author of You Don’t Know JS, defines it as OLOO (Objects Linked to Other Objects).

Let’s go step by step and understand the delegation system.

Prototype Chain

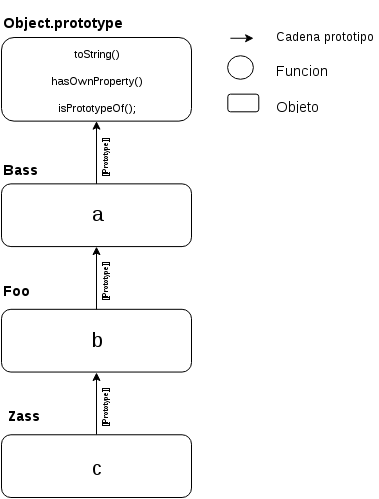

Every object has an internal property [[Prototype]], which is a link that references another object.

[[Prototype]] creates a reference to another object. Most objects have a prototype chain to another object. — Internal Properties

This mechanism is used when a property is referenced on an object and isn’t found on it. That’s when the [[get]] method continues searching in the object linked via [[Prototype]]. This series of links between objects is known as the prototype chain.

Object.prototype

At the top of the prototype chain is Object.prototype. Thanks to this object, we have common methods available on all objects, such as:

- toString()

- valueOf()

- hasOwnProperty( .. )

- isPrototypeOf( .. )

When we create an object literal, it is automatically linked to Object.prototype

Object.create( .. )

To control this link, we can create objects with *Object.create( .. )*, which receives a first argument — the object it will be linked to via [[Prototype]] — and a second argument with the new properties.

Let’s look at an example.

const Bass = { a: 1 };

const Foo = Object.create(Bass);

Foo.b = 2;

const Zass = Object.create(Foo,

{ c: { enumerable: true, value: 3, writable: true } }

)

Zass.hasOwnProperty('a'); //false

Zass.hasOwnProperty('b'); //false

Zass.hasOwnProperty('c'); //true

Bass.isPrototypeOf(Zass); // true

Foo.isPrototypeOf(Zass); // true

Zass.a; // 1

Zass.b; // 2

Zass.c; // 3A graphical representation of this would be:

Object.create(null) creates an object with an empty link, so the object doesn’t delegate anything — it has no prototype chain

Delegating Behaviors

We now know we can manage the link between objects, and this is the key to delegation in JavaScript. This way, we only need to worry about objects and the properties delegated between them.

const switchProto = {

meta: { name: 'interuptor luces' },

state: false,

isOn() {

console.log(this.state);

},

toggle() {

this.state = !this.state;

}

};

const luzSala = Object.create(switchProto);

const luzComedor = Object.create(switchProto);

luzSala.toggle();

luzSala.isOn(); // true

luzComedor.isOn(); // falseAs you can see, we can create two objects and link them to the object we use as a prototype, and their behavior will be independent.

Mutation

Something we need to be careful about is mutation, since objects in JavaScript are dynamic.

If a property is changed on an object, it changes everywhere. Of course, this behavior is expected if you understand how types in JavaScript work.

const switchProto = {

meta: { name: 'interuptor luces' },

state: false,

isOn() {

console.log(this.state);

},

toggle() {

this.state = !this.state;

}

};

const luzSala = Object.create(switchProto);

const luzComedor = Object.create(switchProto);

luzSala.meta.name = 'interuptor de la sala';

console.log(luzComedor.meta.name); // 'interuptor de la sala' MutacióIn the next post, we’ll look at composition, which will help us control this and create an even more powerful inheritance system.

I’d like to share a slightly more complex example, taken from You Don’t Know JS, in its book dedicated to objects.

In this example, we have two controller objects that handle the login form and authentication with the server.

Before reading the example, I recommend understanding how this works.

const LoginController = {

errors: [],

getUser() {

return document.getElementById("login_username").value;

},

getPassword() {

return document.getElementById("login_password").value;

},

validateEntry(user, pw) {

user = user || this.getUser();

pw = pw || this.getPassword();

if (!(user && pw)) {

return this.failure("Please enter a username & password!");

}

else if (pw.length < 5) {

return this.failure("Password must be 5+ characters!");

}

// Se valida correctamente

return true;

},

showDialog(title, msg) {

// Mostrar un mensaje al usuario

},

failure(err) {

this.errors.push(err);

this.showDialog("Error", "Login invalid: " + err);

}

};const AuthController = Object.create(LoginController);

AuthController.errors = [];

AuthController.checkAuth = function () {

let user = this.getUser();

let pw = this.getPassword();

if (this.validateEntry(user, pw)) {

this.server("/check-auth", {

user: user,

pw: pw

})

.then(this.accepted.bind(this))

.fail(this.rejected.bind(this));

}

};

AuthController.server = function (url, data) {

return $.ajax({

url: url,

data: data

});

};

AuthController.accepted = function () {

this.showDialog("Success", "Authenticated!")

};

AuthController.rejected = function (err) {

this.failure("Auth Failed: " + err);

};With behavior delegation, AuthController and LoginController are just objects — we only need to worry about delegating behaviors.

Conclusion

Using behavior delegation can lead to simpler code architectures.

With this approach, we only need to think about objects that delegate behaviors to other objects, which means we don’t end up with rigid hierarchical structures.

“There are two kinds of JS programmers: those of us who learned with JS, and those who learned with another language and try to use JS like that language” — Sergio Xalambri

It might feel a bit unfamiliar at first — especially if you’ve spent a long time using constructors, hierarchies, polymorphism, etc. Understanding how the delegation pattern works takes a little getting used to, but it’s much easier to understand than classical inheritance.